Somewhere just north of the equator it happened.

Neptune, that vindictive Ruler of the Ranging Main, appeared trident and all. He was escorted by a group of insane cronies: a chancery wig donning judge, a sinister looking barber, a mad doctor, and, of course, his queen. Officers dragged me out by my hogtied wrists, pushing me down to my knees in front of the king. The gathered throng quieted as a judge raised her bullhorn and read the falsified charges against me. “You are hereby charged that this day you are present in the domain of His Oceanic Majesty without his consent!” (Boooo!) “You are also charged that on the afternoon of May the 24th, you were seen to fall over on your face in the stern galley!” (Disgusting!) After reading off a few more ginned up charges, she asked “How do you plead: Guilty or Very Guilty?”

Before I could answer, the whole nightmare posse bellowed “Very guilty!”

Neptune — who looked suspiciously like the ship’s Captain — poured a beer over my head, proclaiming “It is the sentence of this court that you be delivered to my physician who will remove the useless contents of your stomach!” Neptune’s queen, feeling left out at this point, cracked an egg on my head as if to get the next sentence across. “You will then be taken to my royal barber,” the king continued, “who will remove your useless hair!”

They dragged me over to the demented surgeon (a dead ringer for the ship’s Customer Affairs officer) who covered me in a white sheet and splayed me out on his table of horrors. He pulled out a large, blood-stained wooden saw that elicited gasps from the crowd then went to work under the sheet, covering the fabric in bright red tomato sauce. “Too blunt,” he yelled, dropping the ineffective tool and reaching for a dagger instead. At this point he placed a plastic bag chock full of half-rotten chum and quadruped guts under the sheet. One at a time he pulled out various organs and pieces of flesh, held them up for everyone to see, and chucked them into a nearby pool of seawater.

With the disemboweling complete, I next faced the deranged barber, who covered me in every sticky and gooey substance available within a thousand miles. He topped off this mad recipe with cracked eggs, flour, and, for good measure, a pie to the face (“Close your eyes,” he whispered to me just before custard surged up my nostrils). After a liberal dousing of half-melted ice cream, he pretended to shave my body with his large wooden straight razor. Then I was off to the pool with the guts and all the other poor souls who had been made to suffer equal or worse punishment.

A loud horn blew and applause followed. Neptune made a final speech pardoning all of his sacrificial victims, myself included. The ritual was complete. I had been granted passage into the Northern Hemisphere.

If this sounds somewhat bizarre, that’s because, well, it is. Then again this particular ship, the RMS St. Helena, has a kind of bizarre mission: to serve as the lifeline to its namesake, one of the most remote inhabited islands in the world.

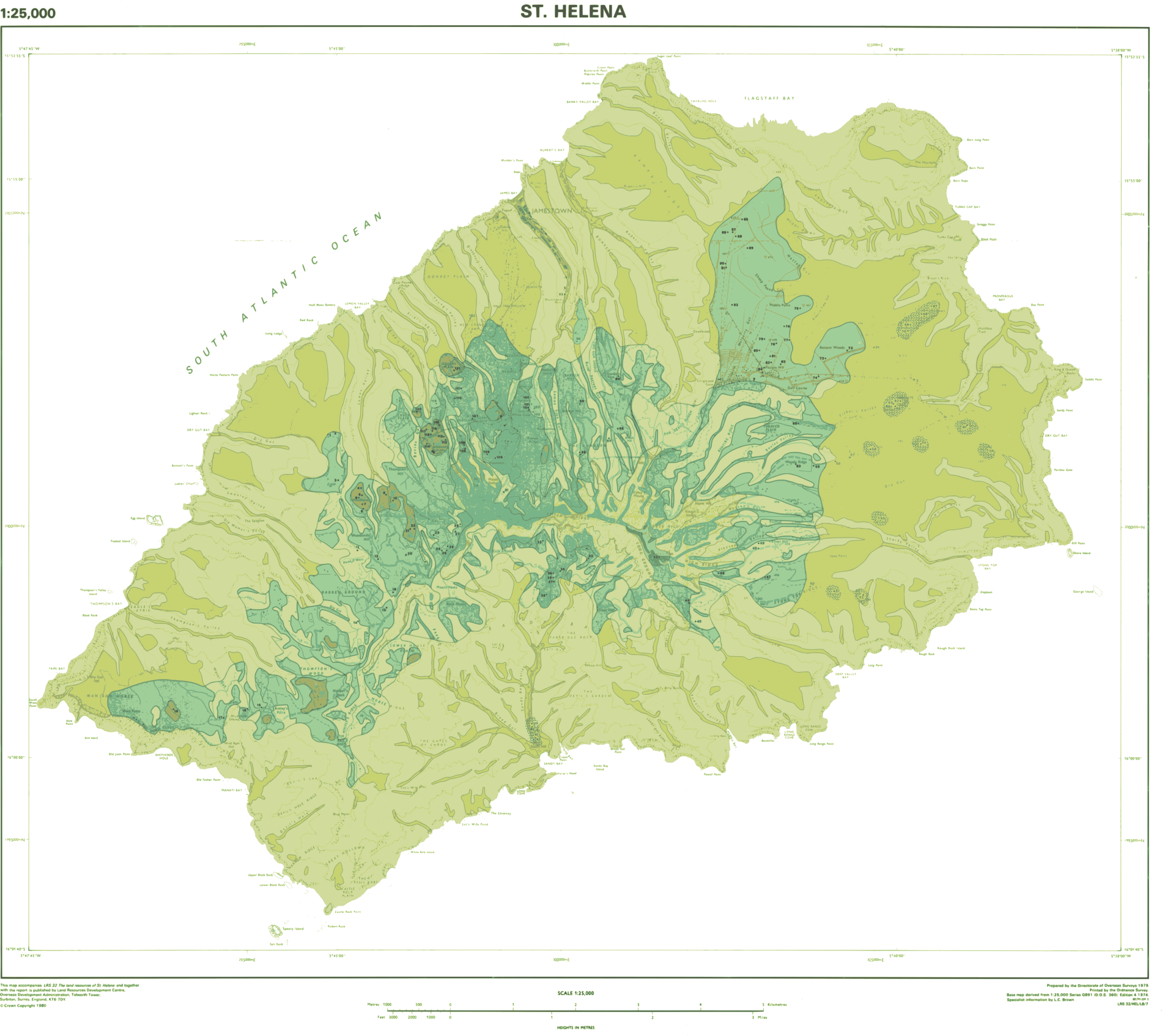

In print it’s been called everything from a “wart on the horizon” to “a halfway house” in the middle of the ocean. A craggy volcanic outcropping spanning a mere 50 square miles, Saint Helena juts out of the South Atlantic 1,200 miles off the coast of Namibia. Today it is classified as a “British Overseas Territory,” and has been governed by one British administration or another since the 16th century. It is most famously known to the rest of the world as the site of the final six years of the exiled Napoleon’s life. And in the 500 years since its discovery it has only been accessible by sea.

The RMS St. Helena remains the sole vessel that regularly makes the journey, a voyage lasting five days over the open ocean from Cape Town. But last May, all of that was set to change.

Thanks to the generosity of British taxpayers, an army of laborers had recently completed the island’s first ever airport — a £285 million gamble with some of the highest stakes around. For the locals, it could open up rapid mobility, not to mention much needed economic opportunity. For the Saint Helena Government, a new era of tourism could be just around the corner. For the UK agencies that subsidize many aspects of life on the island, the airport promises to snag once and for all the elusive white whale of managing imperial legacy: self-sufficiency.

The debut of the airport would be opening night on the world’s stage for a new travel destination, one that the island’s tourism agency bills as “The Secret of the South Atlantic” while simultaneously hoping the secret gets out. But it also spells curtains for the much loved RMS St. Helena, slated for decommissioning after regular flights begin. For a small audience in the middle of nowhere, the whole world was about to be made anew. That is, unless something went terribly wrong.

The trouble started when they actually tried to land a plane. On April 18th 2016, a Boeing 737 had attempted the first test landing on Saint Helena with real passengers. At several hundred feet above the runway, the plane encountered severe and sudden shifts in wind speed and direction — a phenomenon known as “wind shear” — which visibly shook and tossed the aircraft. The pilot had to pull up and make the landing attempt again, and even then it was…let’s just call it rough. One of the test pilots later called the erratic wind conditions “hair-raising.” Suddenly the obscure meteorological phenomenon became a phrase on the lips of just about everyone in the South Atlantic.

The landing proved harrowing enough to scare the Saint Helena Government, the airline, and the agency certifying the airport all into postponing any further scheduled commercial flights until they could figure out what the hell to do. What was supposed to be a celebration of the grand opening on May 21st — which, to salt the wound, is Saint Helena’s national holiday — had now been canceled. Bookings through the single carrier contracted to provide regular flights, Comair, had to be nixed. So much for the official plans.

Down at the Duncan Dock in Cape Town on the day of my departure it was all anyone could talk about. Passengers who had just disembarked from the RMS and those prepping to leave all gathered outside the terminal, milling around and chatting. Generations of connection by sea between Saint Helena and Cape Town have led to tight bonds between the two locales. Saint Helenians — who go by the lofty moniker “Saints” — often come to South Africa to visit friends and relatives, work, or to receive much needed medical care otherwise unavailable at the island’s sole hospital.

Amid all the catching up and rhubarb chatter about a YouTube video showing the test landing, I met Joe and Cheryl Tingler. Joe, a retired air traffic controller originally from Virginia, met and married Cheryl, a Saint, when we was working on nearby Ascension Island decades earlier. The two now split time between a home on Saint Helena and another in Florida — a commute that puts yours to shame. When asked about the airport, Joe shook his head with a kind of You Can’t Make This Shit Up grin, insisting “it was a complete disaster from the beginning.” He went on to say that the runway had been built in the wrong direction, a claim I would hear repeatedly during the course of my visit.

In the succeeding months there would be a flurry of investigations, castigations, and lamentations in the international press and House of Lords, as well as fiery exchanges in the Saint Helenian newspapers. All of these would partially confirm claims that wind problems had always been a known concern. But in that moment, waiting to board the RMS, the enormous fuckup seemed only known to the small community of those affected. And to the Saints it was a cause for worry. This was to be the last passage of the RMS from Cape Town to Saint Helena before its scheduled decommissioning, meaning any Saints who were departing as I boarded would be stranded in South Africa for god knows how long. Any businesses that Saints had started or loans they had taken out in anticipation of a flood of tourists stood in the balance. Everything was up in the air except the goddamn planes.

As the horn of the RMS St. Helena thundered across the Cape, and the ship bobbed slowly out of the harbor, I found myself witness to an unexpected and slowly unfolding controversy.

II

The first thing you need to know about Saint Helena is that its remoteness is more of an historical fact than a geographic one. True, it’s located 1,200 miles from the African coast in a relatively sparse part of the Atlantic. But it was once a heavily trafficked stop along trading routes that swooped around the Southern tip of Africa. Then, in relatively quick order, the island that had been populated during the first great wave of globalization was left behind during the second.

We tend to imagine the ubiquitous corporate titans of our time as leaving few aspects of our lives untouched. We marvel at the Facebooks and Ubers as vanguards of a period of unprecedented change affecting the broadest swath of humanity, hypnotizing everyone with their glowing feeds. And though there’s some truth to this, these companies pale in comparison the the biggest in history. After all, Amazon doesn’t yet forcibly move people around the globe like chess pieces, and Google doesn’t command its own army. Which is why these organizations have nothing on the Goliath of them all: the British East India Company. This world-spanning hybrid of bureaucracy and private military force had as much to do with the creation of our world as any recent “disruptive innovation.” For nearly a century the Company bowled the globe over, forever altering landscapes and societies from North America to the spice islands. Saint Helena is a pockmark in a world covered with the Company’s scars.

The Portuguese first stumbled on the small uninhabited island in 1502, but kept its existence a secret. Only after the East India Company’s establishment of a colony in 1657 was there any population of speak of. Its utility was entirely strategic. The island lay along the Company’s sea route towards colonies in Asia, and was used as a stopgap for refreshing supplies. As late as the first half of the twentieth century, hundreds of ships called there each year. Up until then the island was just as easy to get to as, say, India or China.

For an island that is barely ten miles across, Saint Helena has played an outsized role in world history. Napoleon spent the final years of his life imprisoned there. After the British banned slavery, it became a base for capturing slave ships and liberating their cargo. The island hosted a prisoner of war camp during the Anglo-Boer war, and a century later Saints proudly served in the Falklands War. Edmond Halley, namesake to the comet, visited twice in order to observe a transit of Venus hoping it might lead to the discovery of longitude. Even Charles Darwin made the trip, notably remarking on — surprise, surprise — the windy conditions near what today is the site of the airport.

The current state of affairs where only a single ship makes regular visits is, historically, the aberration and not the norm. The opening of the Suez canal siphoned off shipping that otherwise might have passed through. Planes came to dominate overseas travel in less than a century. Cargo ships got bigger in both size and range. These and other factors brought the island to a level of inaccessibility unknown for hundreds of years. The world simply left Saint Helena behind.

The British have never quite known how to deal with their former colonial possession in the post-colonial era. Saints are today British citizens, but that has only been true since 2002. Twenty years earlier an act of Parliament reclassified the island as a dependent territory, meaning Saints lost the right to even live in the UK. Today the island is classified as a “British Overseas Territory” and its subsidy and funding are, interestingly, administered by the British Foreign Office’s Department of Foreign and International Development (DFID), even though the island is neither foreign nor international. Civil servants from the Foreign Office make up a good chunk of the Saint Helena Government, which means the island is administered largely by temporary appointees shipped in from abroad.

Now, after decades of being pushed to the margins, Saint Helena has been thrust back to the forefront of international news — for unfortunate reasons.

III

When you hear about an island with an ecclesiastic name, you likely picture a tropical paradise — palm trees, fresh coconuts, bikinis, chilled cocktails served on pristine sandy beaches, all that jazz. Saint Helena has none of it.

A series of jagged cliff faces and steep valleys encase the island, making it a kind of natural fortress. There are no beaches in the traditional sense. If there ever were coconuts they have long since been eradicated, and the only cocktail I came across was the much-beloved “shipwreck,” a rum and coke improved in name only. Otherwise locals are satisfied quenching their thirst for booze — which at times seems insatiable — on cheap Namibian beer.

Yet inside that tough shell of an exterior lies an island of rare beauty, with a surprising number of varied landscapes all crammed into 50 square miles. In this bucolic oasis, Saints seem more like country folk than islanders – familiar with each curve of Earth and naming it along the way.

You wouldn’t guess any of this when first arriving in Jamestown. The capital is a thin, mile-long stretch of buildings that runs up a craggy valley from the James Bay, enclosed by steep rocky hills on each side. It is the only town on the island at all, everywhere else being collectively known as “the country.” It hosts the government’s headquarters (“The Castle”), a cathedral, several shops, a museum and archives, and other residences. It also has what is perhaps the weirdest tourist attraction in the world: a staircase. Jacob’s Ladder, as it’s called, is an incline of 700 individual foot-high steps that shoots right up the steep face of Ladder Hill and out of town. Conquering The Ladder is a mandatory rite of passage for all visitors.

- Main Street in Jamestown

- Jacob’s Ladder from the bottom

- Jamestown, with Jacob’s Ladder on the right.

Though it’s remote, Saint Helena has just about all of the conveniences of twentieth-century life. There are plenty of cars on the island. So many, in fact, that Jamestown has a long running problem with parking, and Saints complain about it like an old man bellyaching about the traffic on his street. Electricity, running water, modern construction: check, check, check. There’s also internet service provided by the island’s sole carrier — Sure South Atlantic — though it’s expensive and slow, coming in over a satellite connection.

I heard from more than one traveler that Jamestown reminded them of Britain in the 50s, but being neither British nor geriatric, I had no idea what that meant. To me it seemed like a small country town in the 90s, given the popularity of the DVD rental shop and prevalence of cargo shorts. Only later when I ventured into one of the grocery stores did I get what they might have been talking about: shortages of staple foods and goods are a common and loathed part of life here. The reason is that the RMS brings just about everything that isn’t grown or produced on the island. So while continental country folk have quarterly seasons, Saints have a new paltry harvest every 18 days or so.

Saints themselves have a reputation as cheerful, relaxed people. If any neurotics inhabit the island they must be holed up somewhere and kept from public view. You can hear several variants on the Saint accent all across the island, and in casual conversation they are not difficult to understand. But god help you if they get around and start talking in a group. They are a melange of the many ethnicities that have formed the island’s population in centuries past: white colonists, Chinese laborers, black slaves, and so on. Superficially they claim themselves a to be a racially harmonious society, and this bears out for the most part (one particularly vocal Saint I buddied up with later expressed to me “if you’re white, you’re alright”).

When I first disembarked and checked into my accommodations, I had tea and chatted with the hosts of the Town House B&B, Colin and Marlene Yon. Colin is a stout, older fellow with a medium dark complexion who never rushes a thought. In his living room I noticed a copy of The Sentinel — one of the island’s two newspapers — with the headline Kimley Yon Crowned Miss St Helena 2016. I asked Colin if he was related to her. He paused for a beat and, with a half smile, said “Oh…Probably.” In this small community, there are a dozen or so surnames you hear over and over, and Yon is one of them. “They say it’s a Chinese name. But I don’t think I look Chinese.” He doesn’t.

For visitors, the biggest celebrity on the island is the one who’s been dead for 200 years. Napoleon Street runs through a central part of Jamestown, and several shops offer soap pressed into the shape of the exiled emperor’s head. At the tourism office, you can purchase tickets to view the Napoleonic sites spread across the island — two houses and his tomb. These attractions are actually administered and owned by the French government, who keep a full time consular living on the island. Though it brings in tourism and puts them on the map, some Saints seem ambivalent or even outright hostile towards the legacy of the one time emperor. “He was as big a shit as fucking Hitler!” one local later exclaimed to me during a whiskey soaked conversation.

That first afternoon I spent a few hours walking around town and exploring. In the government archives I found fellow passengers already elbow deep in papers looking for clues about their family history. Over at Anne’s Place, one of the few eateries in town that seemed to be open, a smattering of people sat and ate fried fish over a few beers. Saints lingered along sidewalks, sitting on stoops and chatting with each other, generally cheerful that the RMS was in the harbor. But it was the opposite of bustle. After a couple of hours I thought to myself, what the hell am I going to do here for 10 whole days?

Before long I would come to the conclusion that 10 days wasn’t enough.

IV

In many ways Kevin Hudson is the future of Saint Helena. “I don’t really want to get rich. I just want to be happy and contented,” he told me. “That’s the track I’m on now.” A slender outdoorsman, whose relentless optimism masks his 38 years, Kevin is the kind of person who could easily impress any mother — funny, outgoing, wholesome. He even named his new travel business, Tenka Tours, after the members of his family. I met Kevin in town when the tourism office put us in touch. Ten minutes later we took off together in his pickup truck on an all day, all district tour of the island — my first venture out of Jamestown.

With the airport possibly on the verge of opening, Kevin had recently decided to strike out on his own. “The fact that lots of people are going to come here, I mean, that’s an opportunity. I can show a lot more people Saint Helena, which I’m very proud of.” Kevin seemed to know every inch of the Island, both as a local and as a former employee of the National Trust. His enthusiasm about sharing the island’s history and showing off his favorite places seeped out with each of his rapidly spoken words.

A day out with someone like Kevin and the attraction for any tourist becomes immediately clear. From the ocean, Saint Helena looked mostly like a Chateau D’If in the Atlantic. From Jamestown it seemed like a small, charming, soporific locale. But up in “the country” another world awaited us. This thick, rockbound shell of an island, when cracked, reveals an inner variety of landscapes worthy of a national park: forest, plain, desert, and even dramatically steep pasture land where sheep somehow manage not to topple over. The districts have whimsical, movie poster names like “Half Tree Hollow,” “Deadwood,” and “Fairy Land.” Guiding visitors through this maze of environs could be lucrative business indeed.

- Kevin Hudson and his son Tristan

- Lush, rolling hills common on Saint Helena

- View from Diana’s Peak

- View across part of the island

- The dramatic countryside

- Prosperous Bay Plain in the distance, the site of the airport

Though officially unemployment is low on Saint Helena, so are the wages. As of 2015, the minimum wage is £2.60 per hour and the average annual income was around £8,500. Yet the costs for food and basic services are comparable to those in cities throughout the UK. Many Saints I met had multiple jobs or multiple businesses. Even Kevin works as a freelance handyman when there aren’t many tourists on the island, which is much of the time. “With our lifestyle, you have to be able to accommodate as much as you can yourself in order to survive. You have to be a jack-of-all-trades.”

One of the trades that had come to the island in recent years was construction. Basil Read, a South African company, won the contract to manage and build the airport and became a vital part of life on the island. In addition to troops of African laborers, the company employed many Saints during peak construction. But with the project nearing completion and operations winding down, a large number of Saints will be un or underemployed in the coming months and years.

Prosperous Bay Plain, the site of the airport, looks like a rocky desert. There was little plant life, and sharp winds whipped across the plain. From a hill about a kilometer off we could see the airport runway and terminal building. They sat on the edge of the plain, which ran up to a cliff and dropped almost a thousand feet to the ocean. Kevin recounted his nearly two years working for Basil Read in the earthworks division. “Mammoth task,” he called it. That was an understatement. In order to get the runway to the desired length, Basil Read undertook the single largest earthworks operation in the southern hemisphere, which involved filling in a valley called Dry Gut. “Eight million cubic meters of material, that was. That took two years.” Trucks hauled dirt for 24 hours a day, six days a week. Many thought it would be impossible when the project first started. “And we stuck with it and we did it. Incredible,” Kevin said, still amazed by it all.

But with the airport opening in disarray, it’s unclear how the effort will pay off. I asked Kevin if the news about the delay had him nervous. “I’m not worried. I am disappointed.” He then told me something I would hear again and again, in pubs and on street corners and in private living rooms. “At some stage somebody made a costly mistake, because it wasn’t calculated…wind data has been recorded out in that area since the 70s. I’ve been told that by people that have been doing it. So they knew there was wind issues. And when we learned that the runway, which was originally supposed to be built up the valley as opposed to parallel with the coast — the question is now ‘who changed it?’”

Despite this, Kevin considered the future of the island bright and felt that everyone should stay positive. “We’ve got to think about the future generations. If they see this negative sort of energy now, if they get this negative energy from us, the working class now, it’s going to have a negative impact on them and they’re not going to go anywhere,” adding “People are not going to give up because of this tiny issue. There are ways around it. It’s not the end of it.”

With all of the scenery Kevin had shown me, I began to wonder what opening up the island for tourism would actually mean. So far, little actual development had taken place for accommodating tourists. There were no true hotels, the main Jamestown hotel project only recently picking up steam after years of development hell. Most visitors like myself ended up staying with locals who rent out spare rooms and operate B&Bs. Additionally, restaurants and eateries on the island closed early. Some even required customers to call days ahead of time so the owners knew to be open at all. In order to attract visitors in large quantities, all of that would need to change.

Whether or not this state of affairs could sustain the hoped-for number of tourists — 30k per year, according to one ambitious plan — remained an open question. Could the sudden influx of money spur rapid development? Could that get out of hand? What if it led to such horrors as KFC opening up a location in Jamestown? “A KFC would work here, trust me” Kevin said with a wry smile.

V

In lieu of a balloon-dropping shindig, the government announced an open house at the airport a week before its now indefinitely postponed opening day. Anyone could show up and wander around the new facilities. Not wanting to miss out, I hopped in my rented Ford Focus and began my first attempt at navigating the island’s narrow, twisted roads.

Though Saint Helena is small in square milage, the mountainous terrain ensures that it takes forever to get from one district to another. Traveling between places that appear adjacent to one another on a map can involve hundreds of meters in changing altitude and a dozen cramped turns. Simply driving out of Jamestown can be unnerving. Only two car-width roads provide a way out and both feature steep blind turns. Bays cut out onto the cliff faces provide the only opportunity to let oncoming cars pass, and if you screw this up you simply have to gear into reverse and pray that years of video games have trained you properly.

Saints use their car horns — which they hilariously call “hooters” — prodigiously. The sound can mean everything from Hi Colin, I haven’t seen you in a while to I’m coming around this blind corner so don’t shit yourself. Given the size of the community (and the surprising proportion of its people who are named Colin) there’s a lot of beeping going on. And waving too. One of the great Saintly traditions is that, no matter who comes your way or how much of a rush you’re in, you have to wave to each and every person who passes you. “Don’t get caught not doing that,” I was simply warned.

From Jamestown, the airport can be reached after a 30 minute drive through a few of the island’s districts, including Alarm Forest (“It’s like Beverly Hills,” Kevin had told me) and Longwood, the site of Napoleon’s Longwood House. Then it’s a quick drive along the freshly built highway towards Prosperous Bay Plain.

Even though it was a Sunday evening, many turned up for the open house. Inside the lobby of the terminal, airport staff donning orange vests made feeble attempts to guide groups of visitors around. Everything was in pristine condition, like the interior of a brand new car. People wandered in every direction — through the unstaffed customs area, past the baggage claim, around the check-in counter, all over. It was like being a kid trapped in a shopping mall after closing time. A clearly overwhelmed woman herded a group of a dozen people out towards the runway. I made myself the 13th wheel.

- Testing an airport gate area

- Airport runway on Prosperous Bay Plain

- On the airport runway

She led us up into the control tower, which had a panoramic view of the entire site. Simply put: it looked like a small, modern airport built on the surface of Mars. Sitting near panels of flat screens was Nick Silkstern, an Operational Meteorologist for the UK Met Office who couldn’t have been more than 25 years old. He explained to the group how he monitored the weather conditions, pointing to the gizmos around him. Ships, satellites, infrared, balloons, radar — they had just about every kind of weather measuring method available at the touch of a button. This included methods for tracking wind. “I’ve worked in many sites around the world and I’ve never seen wind so variable,” he said.

- Nick Silkstern in the control tower

Nick pulled up a bird’s eye view of the runway on a computer monitor and explained how, at about 300 meters, wind whips through two very large boulders that rest on a cliff near the end of the runway, creating a swirling vortex that can pass directly through the approach path. Like most natural features on this island, those boulders have names: King and Queen (since in a drunken stupor they look vaguely like monarchs perched on thrones). Though unsure, the Met Office believed that these boulders might play a large role in creating the wind shear.

Shouldn’t someone have known about this? Basil Read had just completed one of the largest earthworks operations in the world. That would have been the time to deal with the rocks. Wouldn’t at least one of the organizations involved have measured conditions well enough to know what needed to be blown up? I asked Nick how long they had been measuring wind conditions at the airport site. “There were studies commissioned, and they did flights across here as far back as 2006. They always highlight [sic] wind shear as a potential problem. And turbulence. But I think the thing that surprised people with the flights that have come in is that the severity is slightly higher.”

A single day of test flights over the airport site did indeed take place in 2006, after which the DFID determined that turbulence at each end of the runway was “acceptable.” But this might have been a slap-dash job. Management consulting firm Atkins had published a feasibility study for the airport project back in 2005 at the behest of the Saint Helena Government and DFID. And wouldn’t you know it? The report expressed “concern” about wind conditions at Prosperous Bay site, saying “there are doubts about the amount of turbulence that could be expected on approaches (due to the elevated location and the surrounding bluffs).” The study recommended a series of test flights over proposed sites “to ensure that the orientation as represented by this Feasibility Study is indeed practicable, not only from a civil engineering point of view but from and aviator’s viewpoint also.”

The study also determined that Boeing aircraft could be “performance limited” in Saint Helena’s wind conditions, and therefore two months’ worth of test flights of 737s should take place over the runway site after it had been completed, at an estimated cost of £500k. Weeks after I returned home this issue would come up in the British House of Lords, where Baroness Anelay, the new Minister of International Development, would imply that by extending the runway there was no longer a need for these test flights. Unfortunately for everyone, the contract with Comair required flying Boeing 737-800s. All of this would lead an editor of The Saint Helena Independent to write “the St. Helena airport project was known to be risky business from the outset.”

Of course, what’s done is done, and while it’s important to track down the causes of this giant cockup, there’s also the pesky little issue of making sure that the quarter of a billion pound airport doesn’t become a Bridge to Nowhere. On this last point Nick seemed confident. “It’s not massively unusual,” he assured me. “No doubt once they’ve looked at the models and we understand it more clearly…we’ll find a way to design airspace and processes to make us able to operate around it.”

By the time I left the airport the sun began dipping below the horizon, and it seemed like the whole damn island trailed on the road behind me. I was driving nervously, white-knuckled. Hooters hooted about god knows what. Somewhere in Alarm Forest the lowering sun screamed directly into my retinas and that’s when it happened — Boom (Whoooshhhhh)!. I had drifted too far sideways, running up on a pointed curb that ripped the front left tire to shreds.

A few hours after hitching a ride back into Jamestown with a couple of sympathetic islanders, I recounted this incident over drinks with a Saint friend — we’ll call him Paul — whom I had met on the ship. When I told him what happened he howled with laughter. Then he raised his brow as if getting a brilliant idea. “That’s it!”

Quick aside: many Saints go by nicknames. It’s not just a casual, cheeky habit among friends. Everyone from grandparents to the island vicars will know it. If you are somehow born into the family of a well-known Saint there is a good chance you could inherit his or her nickname for yourself. Nicknames are so persistent, in fact, that they even appear in newspapers’ reporting on court hearings, which consequently can read like wanted posters from the Old West: THEODORE LAWRENCE also known as BOBBY RECORDS (43) of Teales Cottage had pleaded not guilty to four charges or harassment, of four separate females.

“Blowout, that’s your name!” Paul shouted with a kind of mischievous smirk. Here I was, a total outsider, barely 24 hours on a completely unfamiliar island whose roads I couldn’t navigate, and a Saint had already anointed me in a ritual usually reserved for his own. I could see the headline in the local paper already: ERIC GADE also known as BLOWOUT (32) of USA pleaded guilty to one charge of being a shitty driver.

Like all gossip on Saint Helena, it didn’t take long for word to get around. Within days I heard of people asking “How’s Blowout?” and “Is Blowout coming tonight?” This, I would argue, is the most important miracle that Saints perform: spinning regrettable fuckups into something positive. And they’re going to need such a miracle now more than ever.

VI

The Saint Helena Government headquarters sits right at the mouth of Jamestown. Known as “The Castle,” it’s not the kind of mott and bailey fortress of popular imagination. There are no ramparts, no moats, no prison towers. There are, however, meter-thick walls surrounding the grounds, protecting the complex of colonial style offices from an invasion by sea that is now quite unlikely. Instead of chiseled grey stone, the entire building is coated with a thick sheen of bright white paint. An inlaid stone on one of the walls commemorates its initial construction by the East India Company.

The Company lorded over the island until the mid-19th century and for much of the time its management proved to be a complete disaster. From the jump, colonial administrators worried about finding ways to make the island self-sufficient. Attempts at everything from processing sugar to growing rice all flopped. Planters brought in to settle the island never seemed satisfied with the policies of their appointed overlords (who the hell did they serve anyway — the Company or the Crown?). Many of the administrators themselves weren’t too happy either, which is why several of the attempted mutinies — of which there were plenty — involved company officers. Governors were hired and fired from London with a surprising regularity considering the distances involved. But they persisted. Saint Helena remained one of the Company’s key possessions until the Crown took over in the 19th century.

“I met the CEO and Managing Director of the East India Company in London,” Lisa Phillips told me. Aside from the airport, Ms. Phillips was the biggest item of gossip on the island during my visit. She’s the island’s first female Governor and had arrived mere weeks before, just in time to inherit the airport calamity. “He’s bought all the intellectual property rights from the old one. So for all intents and purposes it’s the same company.” She wasn’t kidding. It turns out the East India Company is in the present day a shop that sells luxury goods like overpriced chocolate and teas. This is a bit like finding out Google has reduced itself to exclusively hawking print ads in the back of Wired magazine. “The irony is he’s Indian,” she added.

Sitting in Governor Phillips’ cavernous office in The Castle, it was easy to see a direct line from the earliest days of rule on the island to the present. While centuries ago Governors were appointed by the company, then later the crown, in more contemporary times the position is assigned by the British Foreign and Commonwealth Office. So there has always been a kind of separation between the office of the Governor and the saints themselves. “They are very colorful, especially under the East India Company,” Governor Phillips said of her distant predecessors with typical British understatement. Aside from the mutinies and constant reassignments, it seems like early Saint Helena governors were always finding new and interesting ways to get themselves killed. My favorite story involves a Governor who tumbled from his donkey and off one of the island’s many cliffs. His death proved far more unique than that of his successor, who was plain old assassinated.

Governor Phillips immediately made a name for herself by refusing to act like administrators of the recent past, who would hole themselves up in Plantation House — the gubernatorial residence — and interact with locals only when absolutely necessary. “There are quite a few Saints who have never been up there. I want to stop that. So on a Sunday afternoon twice a month we’re inviting people to come for tea.” She committed to meeting with every single resident of the island in person by the time her term has ended. On Saint Helena Day she gave a short but effective speech in which she declared “Plantation House is your house. I’m just a lodger.” The Saints loved it.

Many of the locals have hailed her as “a breath of fresh air.” She mixes in with the crowds easily, introducing herself simply as “Lisa” without making a show of it all. In fact, the Governor was so inconspicuous and down to Earth that you might not even realize you’re taking to the island’s top brass.

Two days before our meeting I took an afternoon boat cruise with a dozen or so strangers to try and spot some dolphins. The boat’s owner put out lines to catch fish just in case we got lucky. When one of the lines caught, a woman came and reeled it in (with some assistance). Everyone gathered around and snapped pictures, so I did the same. Only later, back on the island and drinking a cup of tea, did I notice the same woman on cover of one of the newspapers — it was Lisa Phillips. Without knowing it I had taken a photo of the new governor catching a fish.

There’s even a humility to how she got the job in the first place. “I applied. And I’ve not been here before. I just looked it up on the Internet and it looked like good fun, so I thought I’d give it a go.”

Of course, “fun” might be the wrong word for the present circumstance. Governor Phillips had unexpectedly inherited the difficult task of explaining to the island’s residents what exactly is happening with the airport. That hadn’t gone over well. When I told her that Saints I’d spoken with feel like they weren’t being given enough information, she explained how the Government’s strategy was to publish press released in the island’s two newspapers. But the Saints I spoke with viewed them as excessively vague. “I don’t think the press releases are sufficient,” Kevin had told me, for example. “When people here don’t know what’s going on, they become confused an irritated.”

The Governor seemed particularly unfazed by the issue, but also hadn’t had the opportunity to get the full scoop in the limited time she had occupied the post. She echoed the same message as Nick, the meteorologist, that what’s needed is time to measure conditions at the site. She said that the wind shear “is manageable. You just need to know how much there is. We’re doing lots of data collection.” The plan was to pass this information to the pilots who will fly in so that they will know how to handle the conditions. They also needed to explore other options, including smaller planes. But these “further study” explanations have also pissed off the locals. An editorial published two months after my trip in The Sentinel called the government’s communication strategy “Trumpism,” which it defined as follows: “If you don’t know what to do, simply announce that you’re considering the options. It’s working well in America for Trump.” Indeed.

As of this writing, the Saint Helena Government is still seeking bids for carriers that might operate service using smaller aircraft capable of landing on the runway, but the capacity would be significantly lower than that of a 737. And that low number is already a stick in the spokes of the government’s development plans.

The same Atkins consulting report that warned about potential wind problems back in 2005 explicitly concluded that a shorter runway, which would deal with smaller planes, would not have sufficient tourist capacity to reverse what they called the island’s “serious social and economic decline.” Tourism was always the gambit, and high capacity flights would make it possible. Atkins saw this as a path not only to prosperity, but to self-sufficiency. So it’s understandable how, when I asked the Governor which home-grown industries she thought should be promoted, she could only talk about tourism. “When these people come they need to be fed, they need all kinds of things. They need transport, they need things to do on the island, this is all then about employment for Saints, really.”

For the moment, variants of bed and breakfasts are the only accommodation on the island for tourists like myself. Several plans for hotels have fallen by the wayside, though a boutique development in Jamestown has proceeded with pace. “My aspiration is that in all of those tourism related projects, that it will be Saints that are employed.” This includes construction, services, and restaurants. It also includes hospitality, and the Governor insisted that the crew of the RMS are already trained and trained well in this field. But with the ship scheduled for decommissioning, and without any hotels ready to go, there are no appropriate jobs for these soon-to-be jobless saints. When I pointed this out to the Governor she simply replied “I don’t know. Ask them.”

The labor situation on Saint Helena has some odd similarities to the one in my home country. Officially unemployment is low (“There are four people. Four people unemployed on the island,” the Governor told me). But that sunny statistic doesn’t tell us anything about the types of jobs Saints have. Are they full time or part time? How many jobs does a typical Saint have? Wages are also low compared to the cost of living. It’s understandable that people are bewildered and angry. The livelihood of four thousand British citizens is at stake. The DFID seems to have fallen from its donkey and over a cliff.

One can view the airport debacle as simply the latest in a long history of one administration or another mismanaging the island from thousands of miles away. Tourism in the projected numbers — just like sugar, rice, or even flax — runs the risk of becoming yet another failed attempt at catalyzing home grown industry with self sufficiency in mind. And given the placement of the airport project in this long history, it’s worth asking whether or not self-sufficiency is even a worthy goal. Is the cost of subsidizing this unique place truly an unbearable burden for the British?

VII

Back when I first arrived on the island and made my way through the tiny customs office, a woman immediately came up and asked for me by name It turned out to be Coral Moyce — the mother of Cheryl Tingler, the woman I had met at the dock in Cape Town. At some point during the five-day RMS passage, they had called and told her about my arrival. Coral had come all the way down from her home outside of town for the express purpose of greeting me. Such is the hospitality of Saints.

Three days later I puttered out of Jamestown and up Ladder Hill Road in a vintage Land Rover (to many it’s the most desired car model on the island) driven by Coral’s husband, George. Coral, an older woman of youthful exuberance and melodic voice, sat in the back of the truck with teenage posture and a seemingly permanent smile. George, a stoic word-miser, was certainly a badass in his own day, as evidenced by the naked woman tattooed on his forearm. The two had met at a much younger age, when Coral stood front and center at a performance by George’s band. The rest writes itself.

Now, a handful of decades and several children later, they reside above Jamestown in an area called New Ground. If there’s any part of the island that remotely resembled suburban sprawl this would be it, though you’re unlikely to find Cheesecake Factory eating stroller-pushers out on the streets. Instead there are one storey ramblers dotted all over, living up to this rock-solid maxim about Saint Helena: take any landscape you’re familiar with from elsewhere in the world and slant it down at a dramatic slope.

One of the first things George showed me was a framed sun-bleached photo he took in 1964. It depicted a large field of drying flax, the last farm of its kind on the island. He snapped the image weeks before it closed for good. New Zealand flax — the variety that now grows wildly on the island and that many consider a weed — once drove the economy here. The British Post Office used string woven from the flax to tie its packages. Then almost overnight, everything changed: the Post Office switched to nylon string, and the economy of Saint Helena collapsed accordingly. For his generation this was a defining event, one that scattered him and his peers across the South Atlantic to places like the Falklands or Ascension Island — anywhere they could find work at decent pay.

George was eager to share the island’s history. He even popped in a DVD of silent film footage, historical scenes from throughout the decades edited together. But when I asked him if he’d be okay with recording our conversation, he froze up a bit, claiming “I only know what other people tell me.” It’s a common refrain in this close community, where rumor and gossip are virulent. He didn’t have much to say about the airport debacle. He’d seen this before, after all, here in this laboratory of unintended consequences.

Coral made us an elaborate home made meal of vegetables, goat curry, salad, and what can be considered the national dish of Saint Helena, spicy fishcakes. From the delicious cornucopia you’d never guess that back in town the shelves in the grocery store were increasingly barren, now that a few days had passed since the ship came in and the Saints had ransacked the place for every scrap of healthy perishable food.

After lunch we drove over to an area known as Blue Hill to hear some live music. The venue was a place called Moonshine’s, and I learned quickly that the name didn’t reference bootleg alcohol. “You’re here with Coral and George, eh?” the bartender asked me, adding “I’m Moonshine.” A nickname. Of course.

Oddly enough, Saints of all ages enjoy old time country music more than any other genre, almost exclusively so. This doesn’t mean the contemporary, Monday Night Football Ford F-150 riffraff you’d hear on American pop radio stations. Coral described it as “country western,” a reference to an older style. According to the most common explanation, Saints like George working at American bases on Ascension Island picked up a love for the music in the 50s and 60s. This love of country music runs so deep, in fact, that Saints commissioned radio DJ Dave Mitchell to write an unofficial national anthem, My Saint Helena Island, in 1975. The RMS plays this prideful ballad over the loudspeakers every time it embarks from James Bay, leaving some Saints homesick and misty-eyed.

Moonshine’s has a large dance floor that takes up most of the indoor space. Good thing too, because people of all ages slowly filled in to catch a performance of the island’s most famous musical act. Robert Constantine — a.k.a. “Bobby Goose” — is an older gentleman with dad sized glasses and a pristinely silver barber shop part. A man of few words, he tapped out twangy melodies on a monstrous Yamaha keyboard, accompanied by pre-programmed bass and percussion. And the Saints went wild for it. Physicists and philosophers seeking to discover the smallest increment of time imaginable might want to measure the interval between Bobby Goose pressing his first key and someone to jumping up to dance.

Because no party is complete without a clergyman, Coral and George introduced me to their friend Jack Horner, the island’s Anglican priest. Jack is originally from Britain, but like many of the expats here he went and married a Saint (“small-’s’”, he insists). When travelers claim that Saint Helena resembles a British village, they are referring to this kind of situation. The local priest hangs with everyone else, and even downs a few alcoholic drinks without having to transubstantiate anything. In describing the importance of religion in the community, Jack explained to me the difference between marriage (divinely sanctioned) and civil unions (a legal matter), which must have seemed pressing since a widely-discussed proposal to allow gay marriages on the island had generated a vocal backlash.

With the boot-slapping country rhythms and synthesized guitar melodies in the background, a lively discussion of homosexuals, and a dance floor filled with people facing an uncertain economic future — people abandoned by the “globalized” world, alienated from much-needed work and the ability to control their own political destiny — I began to feel much more at home. This could be any community in America that had been left behind in the past half century, the ravaged consequence of decisions made by technocrats in far away places. Moonshine’s could easily be a corner bar in some rust belt town; Bobby Goose a headliner in Wahoo Nebraska. If I was an outsider here, then I was an outsider at home too.

VIII

Much like the only other pub in Jamestown, the Standard, the White Horse sits in a plain building with its windows and doors always open, the sounds inside echoing down the streets. It’s a friendly place in that hilariously crude, dive bar kind of way. Bumper stickers line the wall above the bar. “Jesus Loves You,” begins the best one, “But Everyone Else Thinks You’re An Asshole.”

I had trouble getting Saints to speak with me on record, which was understandable. In a small community like this no one wants to get caught on the bad end of a rumor, and there gossip hangs heavy in the air. One local told me how after walking home from school as a child, his aunt would almost magically know everyone he had spoken to along the way before he even stepped in the door. So while it’s true that Saints are kind and generous, it can be hard to get them to open up, especially to a pasty visitor with a digital recorder.

But many Saints are also booze hounds. It’s not a recent phenomenon. A few decades after the island was initially colonized, settlers nearly deforested the place by using every flammable scrap of wood to distill arrack, a type of spirit made from potatoes. Sure, they may love God first and their families second, but for many the Devil’s Juice comes in at a close third. That’s why I came to the White Horse: to see what a tying one off with a few locals might be like.

It took no time to strike up a conversation with a few of the patrons. Patrick Thomas, the barman, is a slender man in his 50s. To visitors and Saints alike he looks ethnically ambiguous, and has been accused of such unforgivable sins — to his mind — as looking Pakistani, Latin, or even West Indian. We descended almost immediately into drunken gossip. Two others joined us in this endeavor: Colin Thomas (no relation) and a man I came to know simply as Charlie. Colin reminded me of a younger, thinner Gamal Nasser, but with a sing-songy accent and probably very different feelings about the Suez Canal. Charlie looks so much like the actor Clint Howard that I half expected to find his Academy award winning brother around the corner, but unlike the other two I can only understand every tenth word he says.

All of these men insisted that I record as much as possible about what they said, so that the “true” story gets out. I assumed this meant countering the much rosier picture of life on the island commonly presented by fluff-pieces for the tourism office.

Patrick has worked in the White Horse for years. But like many saints, he also has a second job. “I’s the undertaker,” he told me. “He’s the overtaker too,” Colin added, referring to the fact that Patrick doesn’t just prepare the dead, but also drives the island’s single hearse. Several days later I would hear that he keeps a book in which he writes a passage or two about each and every person he’s taken for a final ride. I assumed they were mostly positive.

Though his case is somewhat morbid, it’s not an unusual situation. The precariousness of work on the island often requires Saints to juggle multiple jobs, as Kevin Hudson had mentioned. Many end up seeking work elsewhere, in places like the Falklands or Ascension Island much like George Moyce’s generation. My three drinking buddies could attest to the fact, since they each had done stints on Ascension in the 1970s.

Ascension Island lies 800 miles North of Saint Helena. The island is mainly a communications relay in the South Atlantic, blanketed with satellite dishes and strange mesh arrays of antennae. Aside from the American and British bases where many expatriated Saints work, there isn’t much save the barren landscape. “A pile of cinders” is how one tourist described it to me. It boasts of having “the world’s worst golf course” and the running joke is that Stanley Kubrick filmed the moon landing there.

“I think back in those days we were like bloody slave labor, for the amount of money they paid us,” Colin said, remembering that he made around £32 per week. But that’s not to say they didn’t enjoy it. “It was a prison of pleasure,” Patrick elucidated. “The thing is that everything was done for you.” Food and housing were taken care of. But on the flip side, if they didn’t meet the conditions of the work, they would be sent home. For Patrick, working on Ascension was only a limited-time opportunity anyway. “If you stay on Ascension more than four fucking years you will come home with cancer. The amount of radiation on Ascension, if it don’t fucking kill you, it’ll make you an alcoholic,” he joked in reference to the number of communication dishes. We all clanked glass to that. Charlie added something I couldn’t understand, and everyone laughed.

Contrary to what I had read, they informed me that the real golden era for work on the island was not during the heyday of the flax industry, but rather in the 80s and 90s when the British government was building classified communications towers near Piccolo Hill, not far from the current airport site. Colin and Charlie both worked for Cable and Wireless, the island’s telecom provider. They claimed that during this period of frenetic building wages got up to £5 an hour, which, even without inflation, is notably higher than today’s minimum wage.

Given this rise and fall of labor on Saint Helena over the decades, the importance of bolstered tourism for the locals became even clearer. In the international press, the airport delay had been cast as mostly a boneheaded government flop and disaster for British taxpayers, when, in fact, the future well being of thousands of British citizens hangs in the balance. My companions in the White Horse all seemed disappointed by the delay, but also unsurprised.

At first they were reluctant to speculate about what would become of the airport, though Colin had a kind of bleak outlook. “You see, with this airport business, ay, it’s coming to a close.” The vast undertaking of building the airport — all of the engineers, builders, blasters, and surveyors — all of it was about to go away. In other words, a bunch of Saints were going to be out of the job, and another industry was about the leave the island for good.

Colin also knew for a fact that researchers have been measuring wind out near the site of runway for at least 10 years. “You only had one weather recording station in the middle of the strip. You needed more around. Now when the first plane come in you realize, hey, wind shear, wind, turbulence, things like this — but you already bought the airport. And your investigations were, how do you say? Data about wind out there wasn’t good enough.” The men bickered about where the airport should have been built, but all tended to agree that the current site was flat out the wrong place.

Why Prosperous Bay Plain was chosen as the final site remains one of the most important unanswered questions about the whole fiasco, one that will surely be revealed as investigations play out.

The only possible answer I heard came in the form of a rumor, one that every government official I spoke with skirted around or flatly denied. It went like this: the British Ministry of Defense owns the airstrip on Ascension Island. But in a postwar treaty, they leased out operation of the runway to the Americans for an absurd length of time — through 2048. Given the state of foreign relations, should conflict in the Falklands kick off once again, the Americans might not allow the Brits to land warplanes on the airfield. However, if the British also had a runway long enough to land military aircraft on nearby Saint Helena, well, that would solve the potential problem by providing an air bridge to the Falklands. According to the rumor, this is precisely why the runway was extended, necessitating the earthworks operation of filling in the Dry Gut valley.

“That’s right. That’s exactly right,” said Patrick when I asked about it. He went on to explain just how he thought £283 million in airport project funding was appropriated during Tory austerity. “David Cameron say give Saint Helena the airport, because in 2016 they gonna open the first oil in the Falklands.” The conflict lingers in recent memory with Saints perhaps more than it does with most British. “That’s what we went down there for in 1982 — to secure the fucking Falklands as British sovereignty so that they could have the oil, because the oil’s drying up in the fucking North Sea.” The others seemed to agree with this analysis.

In a way, whether any of this was true or not doesn’t matter. A sizable number of Saints that I spoke with seemed to accept these or other similar speculations, one indication that frustrations with the airport project run deep. For the old timers in the White Horse, the airport delay was merely the latest calamity in a long history of mismanagement of the island. “From the time when it became a Crown Colony,” Colin began, “we were just run by the British government like people from India, Sierra Leone, and everywhere else. They just shit on you and keep you down, and you have a small budget or whatever.”

Though we sat bleary-eyed in a small pub on a remote island thousands of miles from any other landmass, these men were keenly attuned to the outside global forces that affected their lives. Even though some of the specifics might have been rumor, there was and is a cold truth to their perspective. Saint Helena is but one member of an archipelago created by the slow, violent, tectonic forces of globalization, a chain that includes places like St. Louis or Birmingham among its members. Nearly all of these places, until recently, have been silenced by the unintended consequences of technocratic common sense. And though I had overheard some negative discussion of “expats,” this state of affairs hasn’t necessarily translated into a turn towards simplistic nativism, as Charlie reminded me when he said something I could finally understand: “Americans better not have that Trump for President. If Americans have Trump for President that’s —“

“Another World War,” Colin said, finishing the thought.

“He’s the most ignorant fuck,” Patrick piled on.

As the night drew to a close, Colin gave me a serious look and said, “You know, you need to swear more.” Maybe that’s how some Saints deal with their understandable and historic frustrations, through constant punctuated expletives. He then turned to Patrick: “I’m having a fucking shipwreck!”

IX

Even to seasoned ship travelers, the RMS St. Helena can seem like an odd vessel. The 344 foot long ship carries both large shipping containers and passengers — a combination that fell out of fashion as sea travel became a novelty dominated by the giant floating petri dishes of Royal Caribbean, Carnival, and other purveyors of nautical abomination. The RMS also has something you’d never find on one of those behemoths: a working mailbox. If you send a letter to or from the island, it makes part of its journey via this very ship, one of the last few working Royal Mail Ships operating in the world today.

Yet arguably the most important utility of the RMS is that it ferries Saint Helenians and tourists alike to and from the outside world. It is the only vessel that regularly makes trips to the island, and with the air travel indefinitely delayed, remains the sole reliable method for doing so. For visitors crazy enough to go, that turns out to be a kind of blessing: the passage aboard the RMS is as vital a part of the journey as is actually staying on the island.

Aside from the cargo containers, the RMS carries over 100 passengers, complete with hospitality staff, showers, a lounge, sun deck, and all manner of organized activity. The last feature exists to keep passengers from going completely insane. In the isolation of the South Atlantic there would otherwise be little to do or see, the occasional sighting of another ship on the horizon being a notable exception.

The RMS also boasts three square meals a day — four, if you count the smorgasbord of sandwiches, cakes, and cookies that the British humbly call “tea.” Dinner is served in two formal sittings and includes five courses prepared by the finest kitchen staff in the South Atlantic, and perhaps on any ocean. The food is so delicious, so plentiful, that I began to suspect that Saints were cannibals who wanted to fatten up naïve tourists en route to the island. But it turns out that not everything in the world has to be designed for cold, rational, economic efficiency, and Saints exude this attitude. The ship is pleasant simply because some aspects of life can still be pleasant without heeding some abstract, moral bound duty to always turn a profit.

My own journey — allegedly the penultimate — lasted a total of 19 days: 5 from Cape Town to the island, and another 14 from the island to the UK, where the ship then took its farewell tour up the Thames and under Tower Bridge in London. Fellow passengers included a potpourri of people from all over the world: Saints, European and British tourists, government officials, and even a few taking up temporary work on the island. Aside from Saints and their children, the demographic was decidedly older. “There’s nothing else like this in the world” was a common refrain among passengers.

The Saint passengers — who made up about half of the ship — gathered together as if they were at a weeklong family reunion, clustering into small huddles of calm and familiar gossip. Saints brought the neighborhood with them, swapping the sun deck for front porches in Jamestown. In the sun lounge older Saints would sit in the large chairs that bordered the walls around the room. At first I assumed it came from standoffishness, but quickly realized they knew their stuff: these were the most comfortable chairs available on the ship.

Games, dinners, and drink nights all provided chances for travelers and Saints to mingle. The most well attended game was cricket on the deck, played with balls made from rope and with drastically simplified rules. On the inbound voyage the two team captains had unintentionally sorted the sides into more or less tourists versus Saints. As is RMS tradition, the winners would receive a case of Windhoek beer. The Saints destroyed the tourists, after which their team captain, a short and portly fellow with a Burt Reynolds mustache, generously doled out beers to everyone who had played.

drinking, activity, sleep. Repeat. Days on the deck involved losing oneself staring at the blank horizon, where edge of the Atlantic faded into the sky. At night, the views from the deck seemed straight out of a child’s storybook illustration, the moon lighting up the sea for miles with surreal immensity. But during a new moon the nighttime scene proved almost macabre — I could see exactly nothing, only an empty blackness beyond the churning white waves left in the ship’s wake. It was either extremely pleasant or limbo, if there’s even a difference.

News from the outside world would trickle in slowly and make its way around. Though the ship had Internet access, it was prohibitively expensive and a pain to setup. Others had horror stories about turning on their laptops and immediately running up £50 bills due to automatic updates and the like. Each day the crew would print and staple a file with newswire reports from around the world, which would get passed around in the lounges. That proved extra important during our voyages, since there was no shortage of wild headlines: Leicester City had won the Premier League, Donald Trump the nomination, and the airport still stood unused.

The latter point had brought a little chaos to the lives of the crew. Around half of them were Saints, and many I spoke with were not sure what they would do once the ship retired. Yet it became unclear whether or not the RMS would have to be extended in the wake of the airport fiasco. Crewmembers I spoke with were upbeat but anxious. During the outbound passage the shoe dropped: the Captain announced over the PA that the ship would be extended through that September (it was subsequently extended several times, and is still in operation as of this writing). We, the passengers, had found out at the same time as the crew.

John Hamilton, a tall middle aged man with a deep, booming, tobacco-burned voice, serves as the public face of the crew. His plentiful off-color jokes and ship wide PA announcements (“Attention passengers, this is the bureau”) command everyone’s attention. English by birth and Welsh by marriage, he has worked many diverse and odd jobs in his day, everything from salesman to hospitality to a brief stint as “the naked carpenter,” which is exactly what it sounds like. He has worked aboard the RMS on and off for nearly twenty years, beginning in 1996 as Hotel Services Officer. After leaving in 2009 to work aboard a classier vessel, he couldn’t help but return to work again aboard the RMS — even though the new position came with lower rank and pay. “This is by far the best ship,” he told me, when asked about others he has served on.

Yet when it came to the end of the RMS’s tenure, he offered a serious sober analysis. “The majority of the tourists that come to the island come … not only for what is on the island, they come for the ship passage.” The voyage, he says, allows tourists to get acquainted with Saints before arriving on the island, providing a unique tourist perk whose absence may, in his thinking, reduce the allure of Saint Helena.

For Saints who work on the ship, the picture was more uncertain. With hotel projects on Saint Helena stalled there would be few jobs for them to take up back home. The uncertainty about the ship’s future — whether it will be extended indefinitely or not — created other problems for them, Hamilton told me, because they need to stay until the very end in order to get their severance benefits, adding “for some of them that have been here for years, they can’t afford to lose that.” The Saint crew was being asked to sit tight and wait for news, knowing that on short notice this regular source of work could ghost at any moment, after which they would be forced to make a leap in the dark. These were several reasons why Hamilton believed the RMS should have continued regardless of the airport opening.

But the biggest effect of RMS retiring, he said, would be the “impact of the availability of goods on the island.” While discussing the Government’s newly purchased replacement cargo-only ship, he described how “the proposal was for the [new] cargo ship to come every 6 to 12 weeks. We call in every 18 days. And if the island runs out of food every 18 days, then what’s going to happen in 6 weeks?” Though the new ship has four times the capacity of the RMS, perishables would still be a problem and stores would need to increase holdings of frozen and dry goods. “So therefore the cost of living is going to go up,” he told me with a somber grin.

The scenario should sound familiar to people all over the world: the cost of living increases while wages stay flat. How could a plan designed to raise prosperity for Saints end up having precisely the opposite effect?

One flaw appears to have been the audacious projection for tourists — 30k per year — that with his years of experience in hospitality Hamilton found plainly ridiculous. He estimated that even with the planned single flight per week of a full 737, which given the wind problems now seems like a long shot — the island would never hit that number. “You’re never going to get to a point where it’s self-sustainable. The government will still have to put money into it.” Indeed, in the months since I spoke with Hamilton, the British government has published several reports and begun investigations into the airport issue. Most recently, a Committee of Public Accounts report stated explicitly “We are extremely skeptical about the Department’s projected tourism figures and the island’s ability to support such growth in the tourist industry” adding that even with the inflated numbers “the business case for building the airport was marginal at best.” The report goes on to say that further investment in the project will almost certainly be required. In other words the British will subsidize a more expensive airport operation rather than the RMS.

When I asked Hamilton if he felt the airport was a bad investment, he responded tersely in the affirmative. Though the British DFID had been subsidizing life on the island and the operation of the RMS, the amount was “absolutely minute in the coffers of the British government.” The big plan had relied upon big numbers, and seemed like it would worsen the very problem it attempted to solve. Hamilton’s instincts about tourism went beyond the mere capacity of flights. He believes, as many I spoke with did, that Saint Helena proved an attractive tourist destination precisely because of its remoteness. “That’s why people enjoy it. Its isolation from the world.” The perks of this isolation — the trusting society, gregariousness of the people, and the scenery that can seem frozen in time — all of this might be lost if the island became overrun with tourists.

But then again, how much is this aspect of identity worth? As it stood even during my inbound passage, the airport could accommodate small aircraft for emergency medical flights — something never possible before. Shortly after my trip this in fact happened, and a pregnant woman was flown to South Africa for emergency treatment that saved her and her child’s lives. Is this alone worth the £285 million? Who gets to determine if it’s not?

Hamilton believed that even if the airport fails at regular tourism it could still have a different utility, one that we’ve already heard: “I think in ten years…my own personal opinion, and I’ve said it right from the beginning in the open…I personally think it will be an Air Force base.” And perhaps this development could, once again, make Saint Helena a site of strategic importance in foreign affairs like it had been a century before. Hamilton summed up the geopolitics of it simply, saying “America is not welcome in Africa. Britain is. Britain is not welcome in South America. America is,” adding that oil from both continents would be a contributing factor.

Despite possible further extensions, however, the RMS will almost certainly still be retired. When I asked Hamilton what he would miss the most about the ship, he choked up in a way unexpected of men like him. “What am I going to miss the most?” he asked rhetorically, giving him time to force back tears. “I’m going to miss the variety of characters we get onboard this ship. This is what drew me back” to a lower position at lower pay. “The reason I came back was to work with the crew and passengers, because the characters you get on board here make my life…You don’t need Eastenders, you don’t need Coronation Street, you don’t need Neighbors on board here. You just need to watch. You can watch the love stories that grow on board this ship.”

The love story between the Saints and the RMS was initially scheduled to end this past July. My inbound passage, from Saint Helena to the UK over 14 days, served as the vessel’s farewell tour in London. The ship dropped us plebs off in deepest, darkest Essex and continued up the Thames and under tower bridge, mooring along the HMS Belfast and hosting parties featuring third-rate royals, limited tours, and fawning praise.

When it blew its horn in central London, it was presumably for the final time at home. It signaled a collective shout from four thousand British citizens half a world away, citizens who — though constitutionally gregarious and kind — have seen decades of indignation boil over into outright fury.